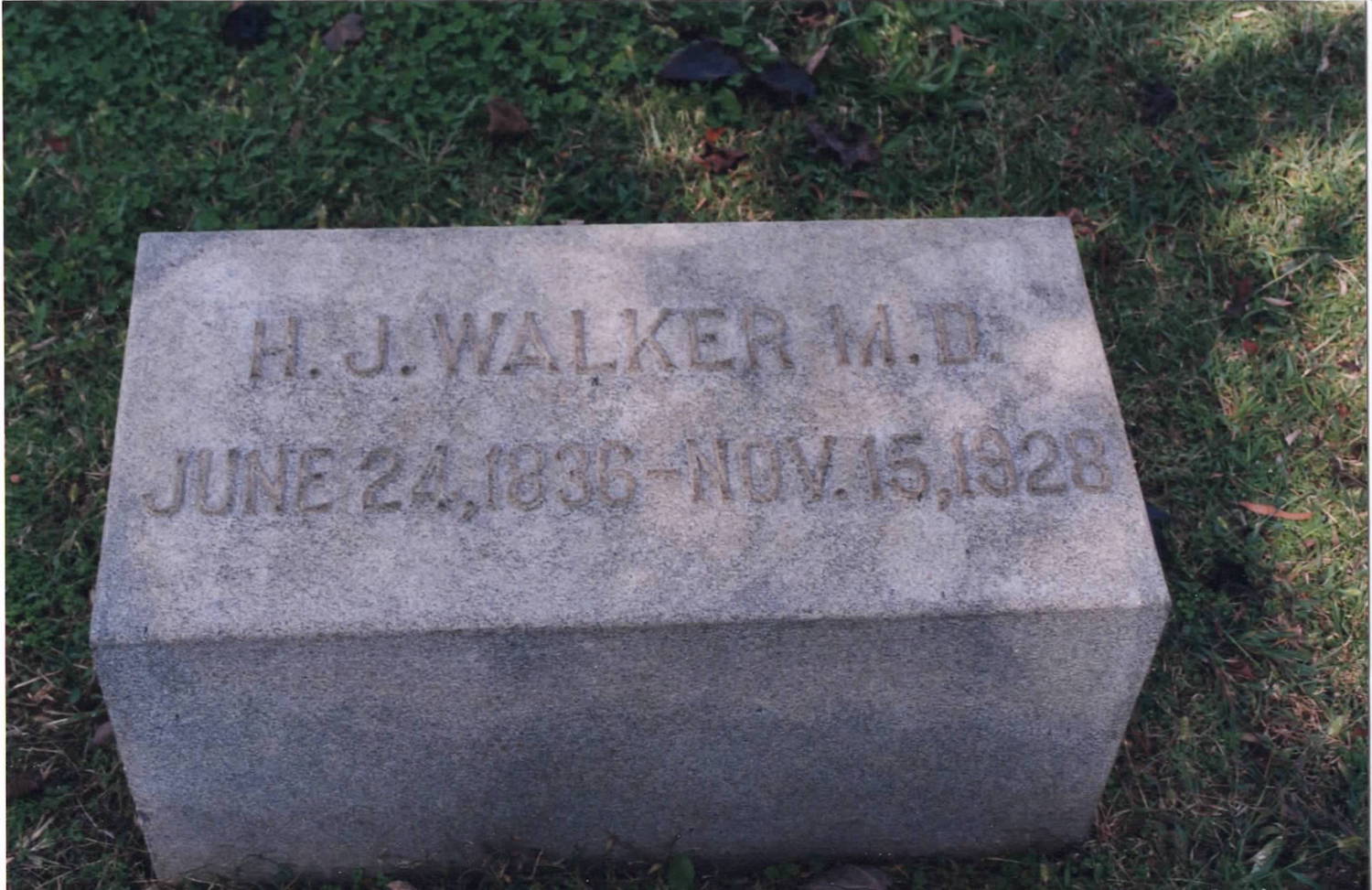

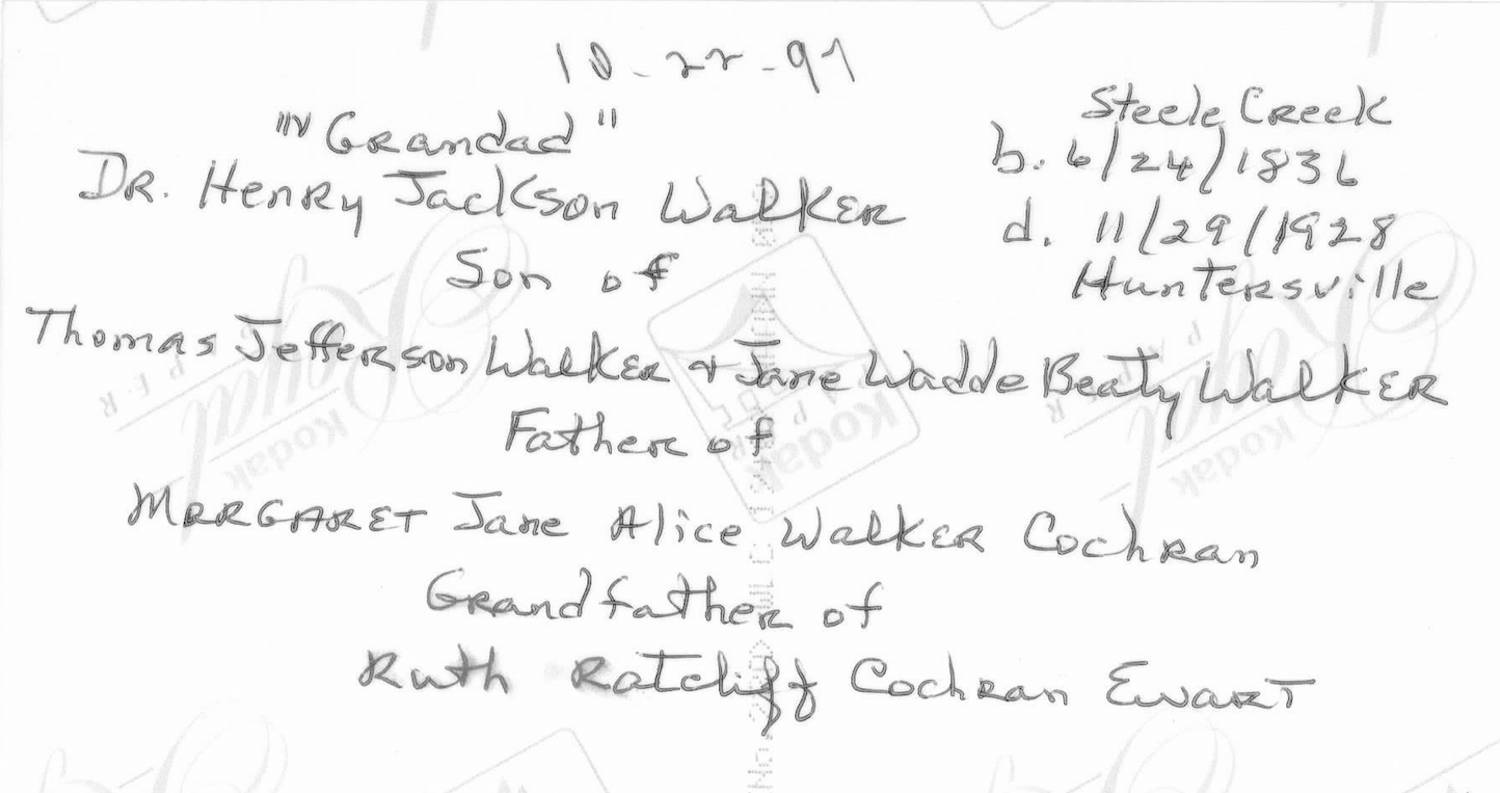

HENRY JACKSON WALKER, M.D.His experience as dictated to his daughter,Mrs. Allie Walker Cochran, November 13, 1917.   Page 1 I was born June 24, 1836, the son of Thomas J. Walker and Jane Beaty Walker

of Steel Creek Community, Mecklenburg County, N.C. I was raised on a farm

and attended the old "Field School" of that community until ready for high

school. I then went to the private school in the Back Creek Community

where Mr. Conner Reid, one of the leaders and teachers of that day, was in

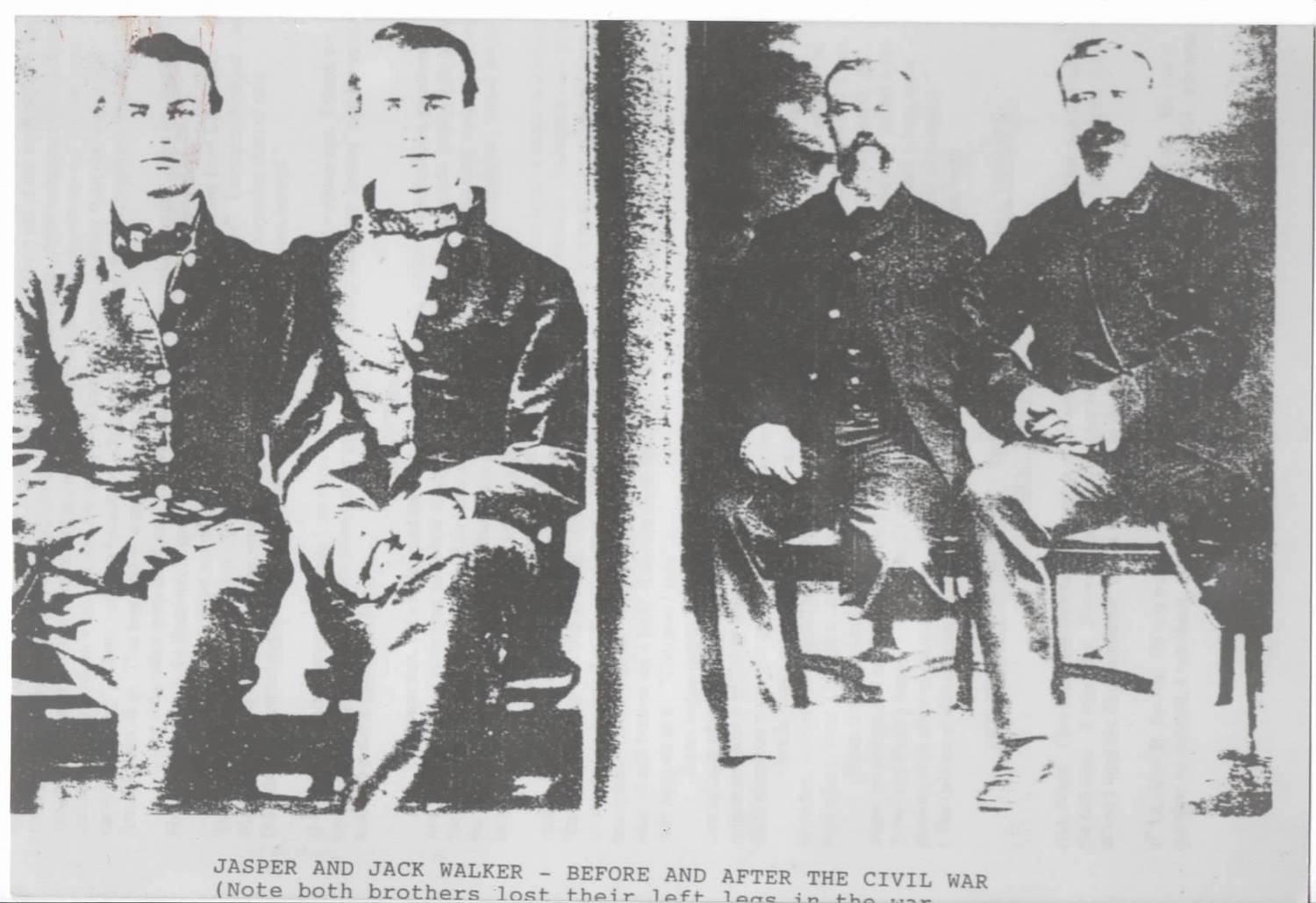

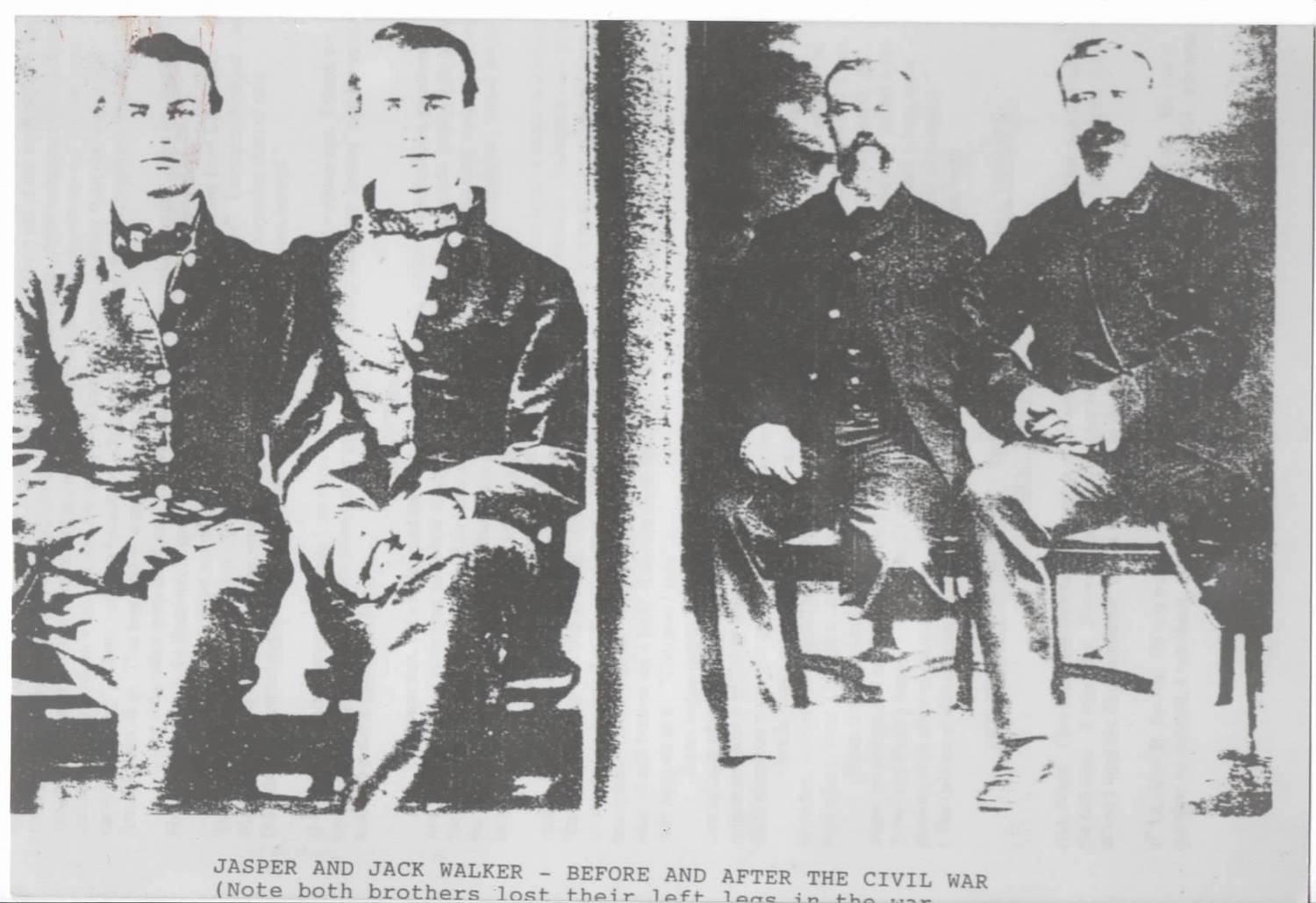

charge. I boarded in the home of Col. Robert M. Cochran, whose younger son

later married my oldest daughter. From there I went to Erskine College in Due West, South Carolina. While there, the Civil War broke out and one night without consulting any of the faculty, thirty-two of us students left school and enlisted in the Confederate Army. We gave as our excuse that we couldn't study and were afraid that the war would be over before we could get there. I was later joined by my younger brother, L. Jasper Walker. Official enlistment was in Charlotte, N.C., April 17, 1861. My sweetheart, Catherine Berryhill, came to Charlotte and helped to make my and others uniforms and to see us off. My brother and I were members of Co. B, 13th Regiment, and our commanding officer was Capt. Burt Ervine. Our company was composed of 110 Mecklenburg boys mostly from the Steel Creek Community. We were entrained in Charlotte for Raleigh where the regiment was being organized. The regiment was commanded by Col. Pender, who later was to be commissioned Brigadier General, and Col. Guy and Major Hamilton. We were moved from Raleigh to Carrysburg, N.C., and from there to Beris Church, Va. Our first battle was at Williamsburg, Va. There seventeen of our company were killed. We had not yet learned to fight. At that time, the female college was in session and we marched into battle as the girls cheered us on. The next battle was Seven Pines, which we won. The next battle was the seven days' fight around Richmond which we won, the Yankees having to take to their gun boats to escape. The next battle was at South Mountain, where General D. H. Hill was in command. We had four brigades which held the enemy in check while Jackson captured Harpers Ferry, September 14, 1862. Two days before we were issued three days rations which was the last we were to receive until September 22. After the above battle, we fell back to Sharpsburg whereon September 17 we were again in battle. After which we recrossed the Potomac River in water over our waists and went into camp until December 12 at the battle of Fredricksburg. That night my brother and I made a bed of pine boughs on the battlefield. The next morning we were covered with six inches of snow. It is said that 500 men contracted rheumatism and some pneumonia from exposure. During the battle and while the Yankees were shelling the town, a little

girl, without realizing the danger, ws amusing herself running after the

round cannon balls. A soldier ran out from his cover and carried her back

to safety. Not knowing what else to do, she stayed with the troops that

night. The next day, marching through town, the child was perched on the

soldier's shoulders until she recognized the mother in the crowd who expressed

her appreciation for the safe-keeping of her child. We went into camp outside of Fredricksburg. On Christmas day the N. C. boys had a snowball fight with the adjoining company from South Carolina, the officers led in the battle. Our next camp was near Mary Baldwin Seminary in Staunton, Va. From there we marched to Chancelorsville where in the battle we were under the command of Stonewall Jackson. We got in behind the Yankee troops and surprised them, some were cooking while others were pitching horseshoes. The enemy was so surprised that they ran. Passing through the camp, I saw an iron pot hanging over the fire. I stuck my bayonet into the big hunk of meat and Bill Clayton held back his great coat and I dropped it into his open haversack, but held it not for long, it was too hot. So we had to carry it on the run as we followed after the Yankees out in the open where others saw it and demanded their share. As we followed the enemy, we came upon a house where we heard screaming. We found two women locked in their cellar by the Yankees. We continued to follow the enemy until dark. General Jackson came to the front in order to reform the lines, and was shot by his own men thinking that he with his staff were the enemy. This catastrophe was not made known to the troops lest they be greatly disturbed. He died a week later with pneumonia brought on by his wound. Until then, this was the greatest loss to the Southern cause. Some even say that this was the turning point of the Civil War. The day following the accidental shooting of General Jackson, General Stewart was in charge of the troops. The Yankees were still in full retreat and in defense set the woods on fire behind them. The Southerners were able to rescue their own wounded and dead but no time to carry out those of the Northern forces and many perished in the fire. Before dawn on the following day, General Pender sent the sharp-shooters to reconnoiter and obtain any information that might give advantage in planning for the battle. Upon reporting, and I was a Sargeant among them, the battle line formed and we proceeded forward. The firing became intense and the sharp-shooters were in the front of the line. During this I saw a large tree a good bit in front of us. I made for it because it offered good protection. The General, seeing me, called out to the soldiers, "Boys, will you let your Sargeant go alone?" At that they all followed in quick order. For this I was promoted to Second Lieutenant. At first opportunity, I told the others what had happened and why. They all laughed and thought it was a huge joke and never held it against me. Our next battle was the three days of Gettysburg. In the first charge at Seminary Hill, my brother, L Jas Walker, was wounded. He was the fifth man to seize the colors when the bearer was shot down, but we captured the battery. This charge is generally known as the turning point of the war, the Rebs reached the stone wall and would have held it if only reinforcements had been quickly sent up to assist us. It is among the records that the Yankees were having their supply wagons moved back as fast as possible, that they had lost the battle.

On the Southern retreat from Gettysburg at Hagerstown, the Yankees were at

our rear and the swollen Potomac in front of us. The sharpshooters held back

the enemy while the Southern Army crossed over the river. It was during this

assignment that I, with many others, was wounded. One P. M., a sixteen-year-

old boy crawled out and gave me his canteen of water. Making a tourniquet

with the canteen strap stopped the flow of blood and saved my life. About

five that evening I was carried off the battle field and laid on the grass in

a private yard until my turn to be operated upon. My leg was amputated just

below the knee after which I was loaded on an ambulance with another man

wounded in the hip. We were taken across the river on a pontoon bridge.

After dark a heavy thunder storm set in and the driver became frightened

and pulled out into a pine field. He unhitched the team and left us there.

The next morning someone heard out calls and we were taken into Martinsburg

and placed in the Methodist Church on planks laid across the top of benches.

We had one blanket and some hay for a pillow. On the second night after

being brought to the church, the man wounded in the hip died after placing

his small treasures in my care with a message for his mother and sweetheart.

He lay there until almost dark the next day before being taken out. We were in the center of contested territory and all the attention this church full of wounded soldiers received was while, during a lull in the fighting, someone would run in and bring us water and food. A little boy sent by his mother would crawl up to me and say, "Lieutenant Walker, my mover (mother) says how are you?" He brought me food and water. In thankfulness, I gave this child my sword. During this time a shabbily dressed, but clean, old man came in asking if anyone had seen Tommie. A Sergeant who was present asked description after which he led him over to a corner and pulled back a cover spread over the dead. Upon seeing his son, he fell upon his knees and offered the most beautiful prayer I had ever heard. He then gave the bundle of clean clothes that he had brought for his son to the Sergeant and he gave them to me in place of the bloody and filthy clothing I had been wounded in. At the end of ten days, the fighting passed from the town and the people of the town coming out of their homes came to the church and carried the wounded into their own homes. I was taken into the home of Billie Riddle. Mr. Riddle had four nieces living with him, he had a son in the Army. These girls nursed me through eight weeks of Camp Fever from which it was a miracle that I recovered. They nursed me and cared for me as tenderly as if I had been their own brother. Later I was told that in my delirium I would call for Katie, my sweetheart. After I was able to be on crutches and move about a little, the family gave a reception in my honor. Their friends with their soldiers all came. One day out walking for exercise, a drunken Yankee soldier came up cursing and threatening. I was hardly able to stand alone. One of the girls stood holding me up and another girl stood between me and the soldier and held him at bay until an officer came along and drove him away.

Not long after this, the Yankee authorities came to take all the wounded

now able to be moved to prison. Uncle Billie had a large store but had no

one to care for it so it had been closed down. He told me if I would but

take the Oath of Allegiance I would not have to go to prison and that I

could take over the store and run it and could have all that was made beyond

taking care of his family. He said not to make answer but to think it over

until morning. The next day the elderly man cme up to me and said "Son,

how about it?" and my answer was, "I can't do it." He stretched out his

hand to me saying, "Son, forgive me for tempting you." That day I was taken

away and sent to Johnson's Island in Lake Erie, forty miles from the Canadian

border. I remained there from September till May when I was exchanged and

allowed to come home April 1, 1864. I came home tired, crippled and defeated. The once beautiful prosperous countryside that I had left was now also tired, crippled and defeated. Only patches here and there had been tended. There were but few farm animals and but little will to work those few. The South was broken and its spirit was gone. I stayed at my Father's home two days not daring to go where I wanted most of all the world to go. At the close of those two days an elderly man walked into the yard. He was a man of few words but direct in the use of those few. "My daughter says that unless you come to see her she will have to come see you. Let's get started." Suddenly the skies lit up, everything was beautiful again and we were on our way. The following month we were married after a seven-year engagement. The wedding was simple. There was nothing new to buy and nothing to buy with. I borrowed a suit from my younger brother. Kate had spun and woven three dresses, but, because I had nothing new, she would not use them and was married in an old black silk of former days. She platted me a hat out of straw and herself one out of corn shucks. Our wedding cake was with sugar she had saved all during the war for this special occasion. We were married June 30, 1864. (Addenda by Dr. Walker's grandson, Rev. Robert M. Cochran)

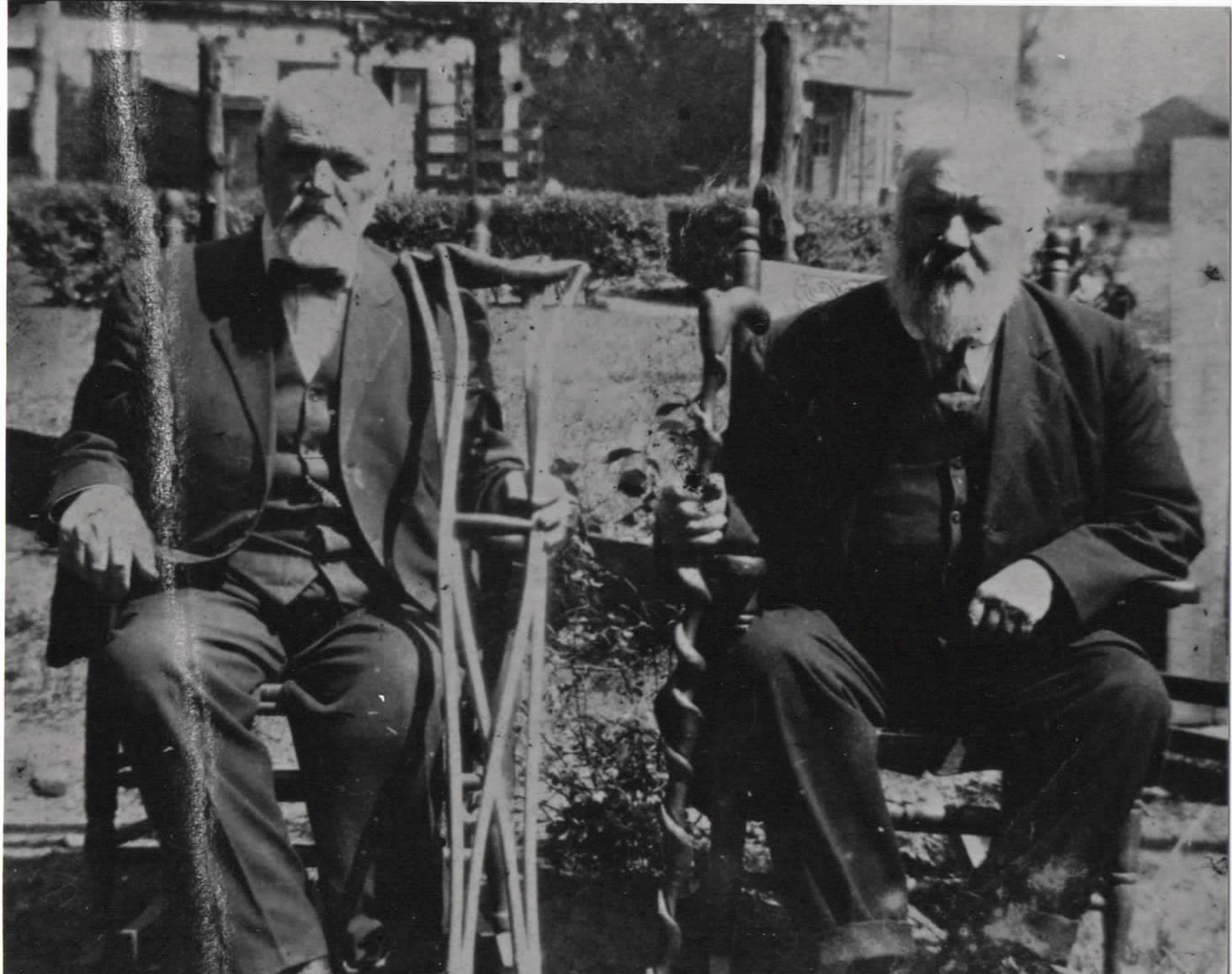

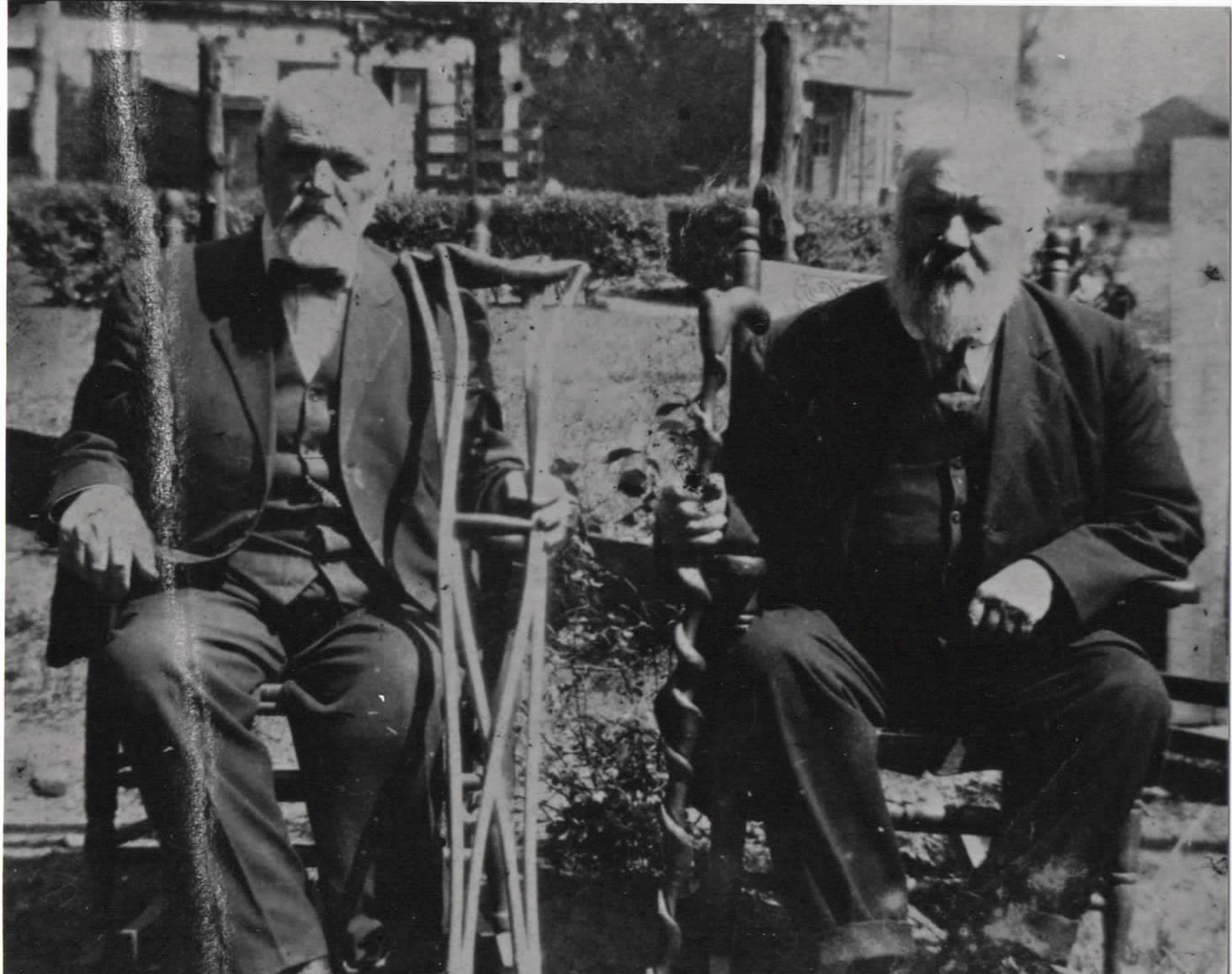

Sometime after the war was over, Grandpa left his Kate and baby daughter,

Allie, and went to New York to study medicine. He never said where the

money came from, but at times mentioned that he kept house for, was janitor,

housemaid, and cook for five Yankee boys who were also medical students.

Thus he was able to finish medical college. Returning home, he built a two-room house and moved his family into it in the little town of Huntersville, 13 miles north of Charlotte. There were five houses at that time including his own. For twenty-eight years he served the peoples of that little town in sickness and in health. A great deal of the time he rode horseback to see his patients. There were but few good roads in those days, especially in winter. Here he raised his family. When the ruggedness of the outdoors began to tell on him, he moved into Charlotte and left his son, Charles, now a doctor in his own right, to carry on. In Charlotte, he started Tryon Drug Co. and later a drug store in North Charlotte. Later he ran for County Treasurer and served for eight years with the help of his youngest daughter, Kittie. About this time his wife died and a little later he fell and broke the hip of his amputated leg. This ended his working days. He must now walk on crutches. Most of his later days were spent in Huntersville in the old home place that he had given to his daughter, Allie Walker Cochran. She moved there with her family in 1912 after her husband died. The old home rattled again with many voices and the pattter of many feet. Finally all the boys of this second generation were grown and gone away. Unable to move around much, he was lonely. More and more Uncle Tom came to pay long visits. Then Uncle Tom was gone. I ventured to ask Dr. Tom Craven what it was that finally took Grand-daddy away November 15, 1928. Dr. Craven smiled and said, "He just got tired of Pettycoats." Few people live to be 94 and few people live to be a blessing to so many. This Grand-daddy was. Always with a cheerful word, even when we knew he was in pain. He loved people and people loved him. Not much more could have been crowded into one life than was in his. Grand-daddy's life was filled with joys and sorrows, hardships and achievements. Each he faced with a depth of faith in God that ensured a blessed heritage for his children and their descendents. (Click on images for larger versions.)

|

Return to:

Walker/Cochran Top of page